No metal without charge

This research article published in Science has been featured in press releases of TU Wien (English version) and Uni Stuttgart (English version), as well as The Academic Times, Physics World and other media.

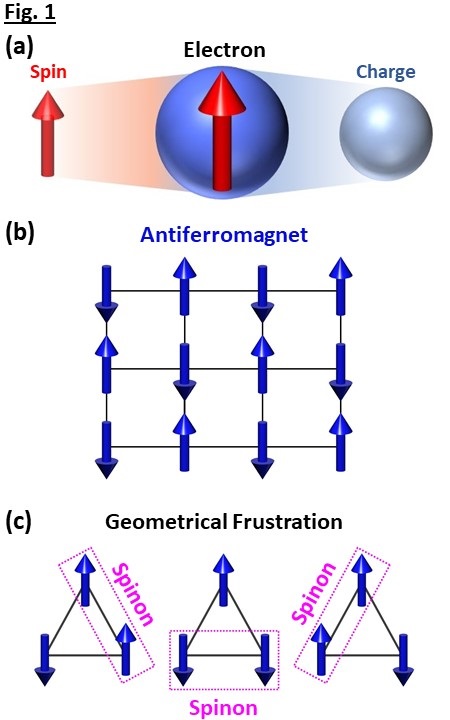

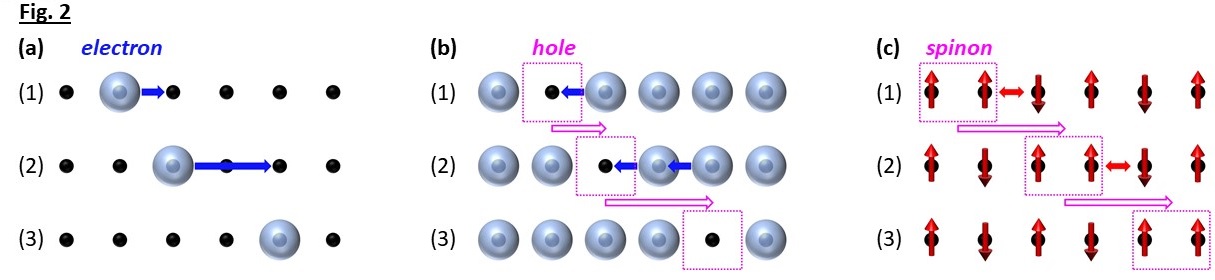

The quantum nature of electrons involves, additionally to their electric charge, a magnetic moment which is known as ‘spin’ (analogue to the induced magnetic field of a rotating charge). One can consider a tiny compass needle (indicated by arrows in Fig. 1) attached to each charge that lines up with an external magnetic field. A spin is the smallest unit of entropy and information, and the total spin of a system is conserved, hence it cannot be simply ‘lost’. In particular, the electron’s magnetic moment interacts much weaker with the crystal lattice than its charge – but can one also selectively transport spins through a solid?

A key requirement are magnetic materials where the orientation of spins primarily depends on that of their nearest-neighbours: in an antiferromagnet the spins are arranged antiparallel to each other in a periodic “up-down” pattern, sketched in Fig. 1b. While this works out nicely on a square lattice, a triangular arrangement of the spins poses an issue: along one of the three directions the unwanted (energetically unfavourable) parallel alignment cannot be avoided, known as geometrical frustration. Such a pair of parallel spins is called ‘spinon’ (Fig. 1c). Yet, how is this related to electrical current?

Effective transport of spin excitations through a solid requires a large number of spinons which, however, are energetically unfavourable and therefore unstable in antiferromagnets. To that end, condensed-matter research has focused on the search for materials where antiferromagnetism is suppressed through geometrical frustration. Since 2003, the organic compound κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3, where the spins are arranged on an almost perfect triangular lattice, has been considered the prime candidate for a spin liquid. A breakthrough has now been achieved in a study published in the journal “Science”, which resulted from work done before Andrej Pustogow's appointment at TU Wien together with international colleagues led by Martin Dressel (Uni Stuttgart). Here, Pustogow identified the spin gap by assessing newly available electron-spin-resonance results, inferring that mobile spinons play no role in this material. “It seems that Mother nature does not like frustration”, says Pustogow, “but rather prefers to arrange the spins in pairs at the cost of a lattice distortion.” Once the spins pair up, there remain no mobile spinons. This way, the hope for a spin liquid with uncharged spinons propagating through the crystal like electrons in a metal had to be abandoned in the case of κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3.

Original article:

B. Miksch, A. Pustogow, M. Javaheri Rahim, A. A. Bardin, K. Kanoda, J. A. Schlueter, R. Hübner, M. Scheffler, and M. Dressel

Science 372, 276-279 (2021),

DOI:10.1126/science.abc6363, arXiv:2010.16155.